The java memory model specifies how the JVM works with the computer's memory (RAM). The JVM is a model of a whole computer so this naturally includes a memory model (the Java memory model).

Knowledge of the Java memory model is needed to design correctly behaving concurrent programs. The java memory model specifies how and when different threads can see values written to shared variables by other threads and how to synchronize access to shared variables when necessary.

# The Internal Java Memory Model

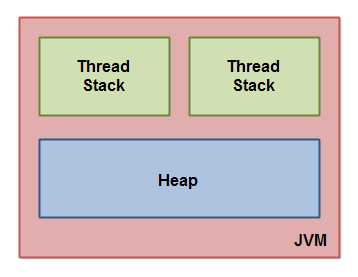

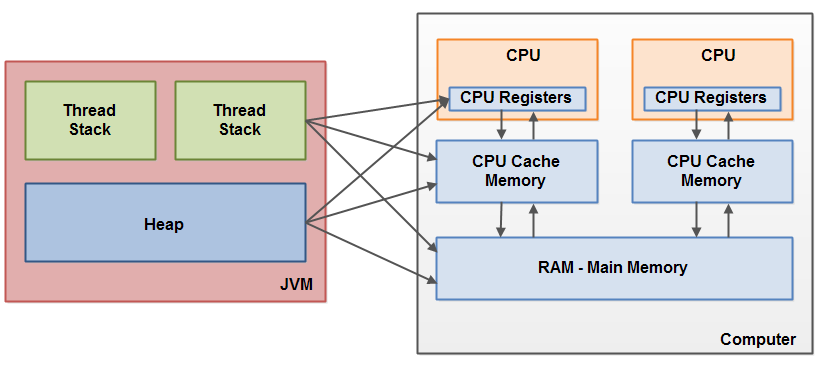

The java memory model used by the JVM divides memory between thread stacks and the heap.

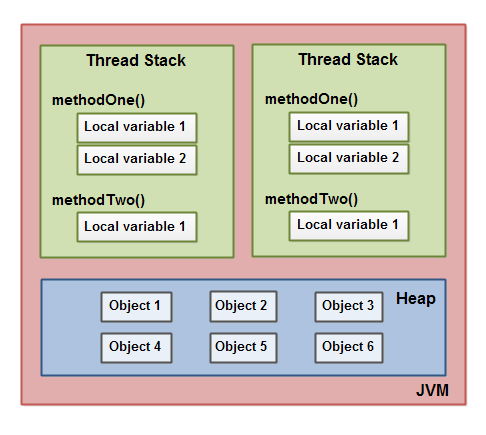

Each thread running in the JVM has its own thread stack - usually called the "call stack". The stack contains information about the methods the thread has called to reach the current point of execution.

* A local variable may be of a primitive type, in which case it is totally kept on the thread stack.

* A local variable may also be a reference to an object. In that case the reference (the local variable) is stored on the thread stack, but the object itself if stored on the heap.

* An object may contain methods and these methods may contain local variables. These local variables are also stored on the thread stack, even if the object the method belongs to is stored on the heap.

* The Heap contains all objects created in your application, regardless of what thread created the object.

* An object's member variables are stored on the heap along with the object itself. That is true both when the member variable is of a primitive type, and if it is a reference to an object.

* Static class variables are also stored on the heap along with the class definition.

Objects on the heap can be accessed by all threads that have a reference to the object. When a thread has access to an object, it can also get access to that object's member variables. If two threads call a method on the same object at the same time, they will both have access to the object's member variables, but each thread will have its own copy of the local variables.

# Hardware Memory Architecture

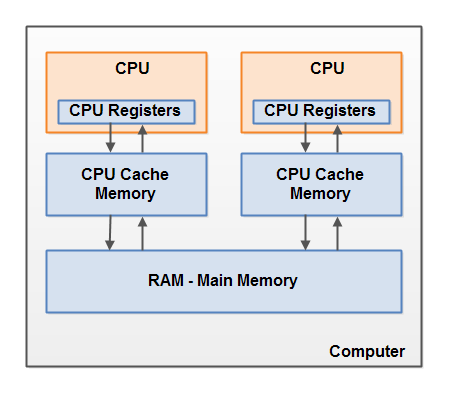

Modern hardware memory architecture is a bit different from the internal Java memory model. It is important to understand the hardware memory architecture too, to understand how the Java memory model works with it.

A modern computer often has 2 or more CPUs in it. Some of these CPUs may have multiple cores too. Therefore, it is possible to have more than one thread running simultaneously. Each CPU is capable running one thread at any given time.

Each CPU contains a set of register which are in-CPU memory. The CPU can access the registers much faster than it can access main memory. Therefore, the CPU can perform operations much faster on these registers than it can perform on variables in main memory.

Most modern CPUs have a cache memory layer of some size. The CPU can access its cache memory much faster than main memory, but typically not as fast as it can access its internal registers. Some CPUs may have multiple cache layers (Level 1, Level 2, ...), but is not so important to understand how the Java memory model interacts with memory. What matters is to know that CPUs can have a cache memory layer of some sort.

A computer also contains a main memory area (RAM). All CPUs can access main memory. The main memory area is typically much bigger than the cache memories of the CPUs.

Typically, when a CPU needs to access main memory, it will read part of main memory into its CPU cache. It may even read part of the cache into its internal registers and then perform operations on it. When the CPU needs to write the result back to main memory, it will flush the value from its internal register to the cache memory, and at some point flush the value back to main memory.

The values stored in the cache memory will typically be blushed back to main memory when the CPU needs to store something else in the cache memory. Typically, the cache is updated in smaller memory blocks called "cache lines". One or more cache lines may be read into the cache memory, and one or more cache lines may be flushed back to main memory again.

# Bridging The Gap Between The Java Memory Model And The Hardware Memory Architecture

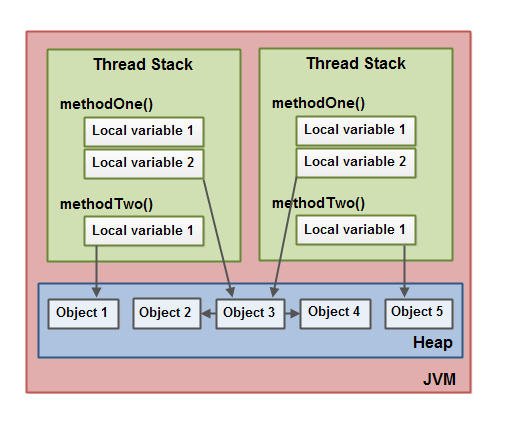

The Java memory model and the hardware memory architecture are different. The hardware memory architecture does not distinguish between thread stacks and heap. On the hardware, both the thread stack and the heap are located in main memory. Parts of the thread stacks and heap may sometimes be present in CPU caches and in internal CPU registers as illustrated below.

when objects and variables can be stored in various different memory areas in the computer, certain problems may occur. The two main problems are:

* Visibility of thread updates (writes) to shared variables.

* Race conditions when reading, checking, and writing shared variables.

# Visibility of Shared Object

If two or more threads are sharing an object, without the proper use of either `volatile` declarations or `synchronization`, updates to the shared object made by one thread may not be visible to other threads.

Imagine that the shared object is initially stored in main memory. A thread running on CPU one then reads the shared object into its CPU cache. There it makes a change to the shared object. As long as the CPU cache has not been flushed back to main memory, the changed version of the shared object is not visible to threads running on other CPUs. This way each thread may end up with its own copy of the shared object, each copy sitting in a different CPU cache.

To solve the problem illustrated above, the `volatile` keyword can make sure that a given variable is read directly from main memory, and always written back to main memory when updated.

# Race Conditions

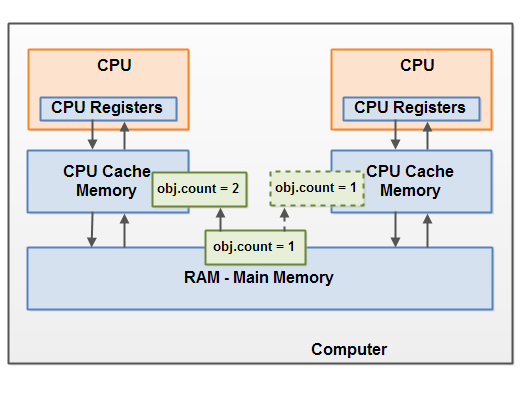

If two or more threads share an object, and more than one thread updates variables in that shared object, [race conditions](https://jenkov.com/tutorials/java-concurrency/race-conditions-and-critical-sections.html) may occur.

Imagine if thread A reads the variable `count` of a shared object into its CPU cache. Imagine too, that thread B does the same, but into a different CPU cache. Now thread A adds one to `count`, and thread B does the same. Now `var1` has been incremented two times, once in each CPU cache.

If these increments had been carried out sequentially, the variable `count` would have been incremented twice with the original value + 2 written back to main memory.However, the two increments have been carried out concurrently without proper synchronization. Regardless of which of thread A and B that writes its updated version of `count` back to main memory, the updated value will only be 1 higher than the original value, despite the two increments.

To solve this problem you can use a [Java synchronized block](https://jenkov.com/tutorials/java-concurrency/synchronized.html). A synchronized block guarantees that only one thread can enter a given critical section of the code at any given time. Synchronized blocks also guarantee that all variables accessed inside the synchronized block will be read in from main memory, and when the thread exits the synchronized block, all updated variables will be flushed back to main memory again, regardless of whether the variables are declared volatile or not.